Python is a powerful programming language that is easy to learn and easy to work with, but it is not always the fastest to run—especially when you’re dealing with math or statistics. Third-party libraries like NumPy, which wrap C libraries, can improve the performance of some operations significantly, but sometimes you just need the raw speed and power of C directly in Python.

Cython was developed to make it easier to write C extensions for Python, and to allow existing Python code to be transformed into C. What’s more, Cython allows the optimized code to be shipped with a Python application, so there is no need for the user to compile it.

With a major new release on the way, now is a great time to get started with Cython. This tutorial walks through the steps needed to transform existing Python code into Cython and use it in a production application.

A Cython example

Let’s begin with a simple example taken from Cython’s documentation. Below is a not-very-efficient implementation of an integral function:

def f(x):

return x ** 2 - x

def integrate_f(a, b, N):

s = 0

dx = (b - a) / N

for i in range(N):

s += f(a + i * dx)

return s * dx

This code is easy to read and understand, but it runs slowly. This is because Python must constantly convert back and forth between its own object types and the machine’s raw numerical types.

Now consider the Cython version of the same code:

import cython

def f(x: cython.double) -> cython.double:

return x**2 - x

def integrate_f(a: cython.double, b: cython.double, N: cython.int) -> cython.double:

i: cython.int

s: cython.double = 0

dx: cython.double = (b - a) / N

for i in range(N):

s += f(a + i * dx)

return s * dx

Cython allows us to explicitly declare variable types throughout the code, so that the Cython compiler can translate those “decorated” additions into C.

Cython syntax

Originally, Cython used special keywords that weren’t found in conventional Python syntax. This made Cython code reminiscent of a hybrid of Python and C, but also made such code impossible to analyze with Python’s code-linting tools.

The new “pure Python” syntax for Cython uses Python’s own syntax—decorators, type annotations, context managers—to be fully compatible with Python and its code-linting tools. The new Cython syntax also lets you write code that still runs, albeit without Cython’s speed, in regular Python. This works as a fallback mechanism for when only the “un-Cythonized” version of the code is available.

For the sake of this article we’ll use the pure Python syntax, but you can read more about the earlier syntax in Cython’s documentation, which presents examples in both syntaxes.

The cython namespace

Before you can use any of Cython’s functionality in a program, you need to import the cython namespace. The cython namespace contains all the Cython-related components you can add to a Python program to transform it to a Cython program.

Variable types and type annotations

By default, Cython variables are Python types. You use type annotations to indicate the use of a Cython type—e.g., x: cython.long, as in the above example.

Some of the variable types used in Cython are the C equivalents of Python’s own types, such as int, float, and long. Other Cython variable types are also found in C, like char. And others are unique to Cython, like bint, a C-level representation of Python True/False values.

The cfunc decorator

Functions written in Cython only using Python’s def keyword are visible to other Python code, but incur a performance penalty. The cython.cfunc decorator indicates the function in question is a pure C function. It’s only visible to other Cython or C code, but if properly typed it can execute much faster. Any functions only called internally from within a Cython module should use cython.cfunc.

We’ll explore how to use cython.cfunc a little later.

The gil/nogil context managers

These context managers are used to delineate sections of code that require (with cython.gil:) or do not require (with cython.nogil:) Python’s Global Interpreter Lock, or GIL. C code that makes no calls to the Python API can sometimes run faster in a nogil block, especially if it’s performing a long-running operation.

You don’t need to know all the Cython namespace objects in advance. Cython code is often written incrementally—first you write valid Python code, then you add the Cython decoration to speed it up. Thus you can pick up Cython’s extended keyword syntax piecemeal, as you need it.

Compile Cython

Now that we have some idea of what a simple Cython program looks like, let’s walk through the steps needed to compile Cython into a working binary.

To build a working Cython program, we’ll need three things:

- The Python interpreter (CPython). Because Cython development lags slightly compared to work on CPython itself, it’s often a good idea to use a version that’s one release behind the current one. So, if the most recent release is 3.13, use 3.12.

- The Cython package. You can add Cython to Python by way of the

pippackage manager:pip install cython. - A C compiler.

The last item can be tricky if you’re using Microsoft Windows as your development platform. Unlike Linux, Windows doesn’t come with a C compiler as a standard component. To resolve this, grab a copy of Microsoft Visual Studio Community Edition, which includes Microsoft’s C compiler and costs nothing. You can also install the needed components using winget using the following command:

winget install Microsoft.VisualStudio.2022.BuildTools --force --override "--wait --passive --add Microsoft.VisualStudio.Component.VC.Tools.x86.x64 --add Microsoft.VisualStudio.Component.Windows11SDK.22000"

Cython programs have historically used the .pyx file extension. You can use .pyx to distinguish Cython from other Python modules, even if you’re using the pure-Python syntax, but you can use plain old .py as well. Just remember to set your linter to recognize .pyx files if you use that extension in pure-Python mode. For the examples in this article, we’ll use .pyx.

In a new directory, create a file named num.pyx that contains the Cython version of the integral function shown above (the second code sample under “A Cython example”) and a file named main.py that contains the following code:

from num import integrate_f

print (integrate_f(1.0, 10.0, 2000))

This is a regular Python program that will call the integrate_f function found in num.pyx. Python code “sees” compiled Cython code as just another module, so you don’t need to do anything special other than import the compiled module and run its functions.

Finally, add a file named setup.py with the following code:

from setuptools import setup, Extension

from Cython.Build import cythonize

ext_modules = [

Extension(

"num",

["num.pyx"],

)

]

setup(ext_modules=cythonize(ext_modules, annotate=True))

setup.py is normally used by Python to install the module it’s associated with, and can also be used to direct Python to compile C extensions for that module. Here we’re using setup.py to compile Cython code.

You can then compile the .pyx file by running the command:

> python setup.py build_ext --inplace

If the compilation is successful, you should see new files appear in the directory: num.c (the C file generated by Cython) and a file with either a .o extension (on Linux) or a .pyd extension (on Windows). That’s the binary the C file has been compiled into. You may also see a build subdirectory, which contains the artifacts from the build process.

Run python main.py, and you should see something like the following returned as a response:

283.297530375That’s the output from the compiled integral function, as invoked by our pure Python code. Try playing with the parameters passed to the function in main.py to see how the output changes.

Note that whenever you make changes to the .pyx file, you will need to recompile it. Of course, any changes you make to conventional Python code will be affected immediately.

The resulting compiled file has no dependencies except the version of Python it was compiled for, and so can be bundled into a binary wheel. Note that if you refer to other libraries in your code, like NumPy (see below), you will need to provide those as part of the application’s requirements.

How to use Cython effectively

Now that you know how to “Cythonize” a piece of code, the next step is to determine how your Python application can benefit from Cython. Where exactly should you apply it?

For best results, use Cython to optimize these kinds of Python functions:

- Functions that run in tight loops, or require long amounts of processing time in a single “hot spot” of code.

- Functions that perform numerical manipulations.

- Functions that work with objects that can be represented in pure C, such as basic numerical types, arrays, or structures, rather than Python object types like lists, dictionaries, or tuples.

Python has traditionally been less efficient at loops and numerical manipulations than non-interpreted languages. The more you can decorate your code to indicate it should use base numerical types that can be turned into C, the faster it’ll be able to crunch numbers.

Using Python object types in Cython isn’t itself a problem. Cython functions that use Python objects will still compile, and Python objects may be preferable when performance isn’t the top consideration. But any code that uses Python objects will be limited by the performance of the Python runtime, as Cython will generate code to directly address Python’s APIs and ABIs.

Another worthy target of Cython optimization is Python code that interacts directly with a C library. You can skip the Python “wrapper” code and interface with the libraries directly.

However, Cython does not automatically generate the proper call interfaces for those libraries. You will need to have Cython refer to the function signatures in the library’s header files, by way of a cdef extern from declaration, which is only possible in Cython’s legacy mode. However, you can use declaration files to allow pure-Python Cython code to work with external declarations.

Note that if you don’t have the header files, Cython is forgiving enough to let you declare external function signatures that approximate the original headers. But use the originals whenever possible to be safe.

One external C library that Cython can use right out of the box is NumPy. You can simply import numpy as before and use all of NumPy’s functionality. However, to get the best possible results, you’ll want to use proper type annotations on your code. This ensures the Cython compiler understands you are working with NumPy types and not generic Python object types.

Cython profiling

The first step to improving an application’s performance is to profile it and generate a detailed report of where time is spent during execution. Python provides built-in mechanisms for generating code profiles. Cython not only hooks into those mechanisms but has profiling tools of its own.

Python’s profiler, cProfile, generates reports that show which functions take up the most time in a given Python program. By default, Cython code doesn’t show up in those reports. However, you can enable profiling on Cython code by inserting a compiler directive at the top of the .pyx file with functions you want to include in the profiling:

# cython: profile=True

You can also enable line-by-line tracing on the C code generated by Cython. Doing this imposes a lot of overhead, so it’s turned off by default. (Profiling generally imposes overhead, so be sure to toggle it off for code that is being shipped into production.)

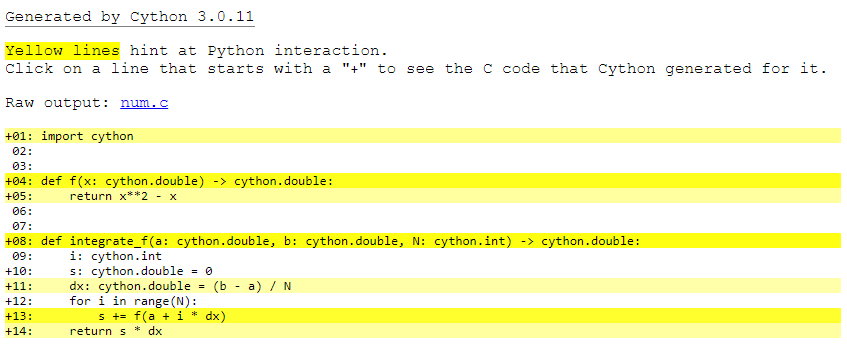

Cython can also generate code reports that indicate how much of a given .pyx file is being converted to C, and how much of it remains Python code. The setup.py file from our example specified this with the annotate=True statement in the cythonize() function.

Delete the .c files generated in the project and re-run the setup.py script to recompile everything. When you’re done, you should see an HTML file in the same directory that shares the name of your .pyx file—in this case, num.html. Open the HTML file and you’ll see the parts of your code that are still dependent on Python highlighted in yellow. You can click on the yellow areas to see the underlying C code generated by Cython.

A Cython code annotation report. The yellow highlights indicate parts of the code that still depend on the Python runtime.

IDG

In this case, the def f function is still highlighted in yellow, despite having its variables explicitly typed. Why? Because it’s not annotated explicitly as a Cython function. Cython assumes any function not annotated with @cython.cfunc is just a Python function, and not convertible to pure C.

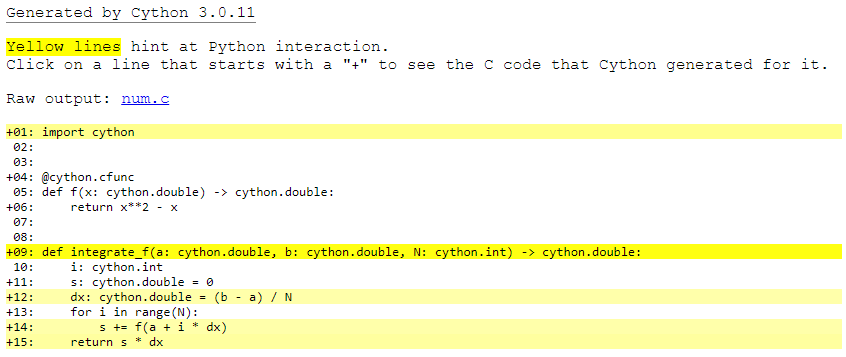

You can fix this by editing the def f declaration to read:

@cython.cfunc

def f(x: cython.double) -> cython.double:

Save and recompile the file, and reload the report. You should now see the def f function is no longer highlighted in yellow; it’s pure C.

The revised Cython function, now pure C, generates no highlights.

IDG

Note that if you have profiling enabled as described above, even “pure” C functions will show some highlighting, because they have been decorated with trace code that calls back into Python’s internals.

Also note that the division operation in line 12 is also highlighted; this is because Cython automatically inserts tests for division by zero, and raises a Python exception if that’s the case. You can disable this with the cdivision compiler directive, or by way of a decorator on the function (@cython.cdivision(True)).

Cython resources

Now that you have some idea of how Cython integrates with an existing Python app, the next step is to put it to work in your own applications, and to make use of other resources out there:

- The official Cython documentation is your best next step. It contains many tutorials that cover separate aspects of Cython, such as working with Python’s native array datatype.

- The Cython code repository on GitHub also has a wiki with useful tips.

- If you have a question that isn’t covered by the docs, ask in the official cython-users mailing list. Cython’s core developers read the list and provide highly technical, detailed answers.

- You’ll find a treasure trove of Cython questions and answers on Stack Overflow. If you have a specific technical question about using Cython, odds are someone has already answered it.

- Kurt Smith has written a book-length exploration of working with Cython that covers various features of Cython and details many usage scenarios. However, it is dated 2015 and hasn’t been revised to cover the most recent additions to Cython.

- Another useful book is High Performance Python by Micha Gorelick. It isn’t as comprehensive as Smith’s book as far as Cython goes, but offers a broader perspective on Cython as one among several technologies that can be used to improve the performance of Python applications. This book was last revised in 2020.